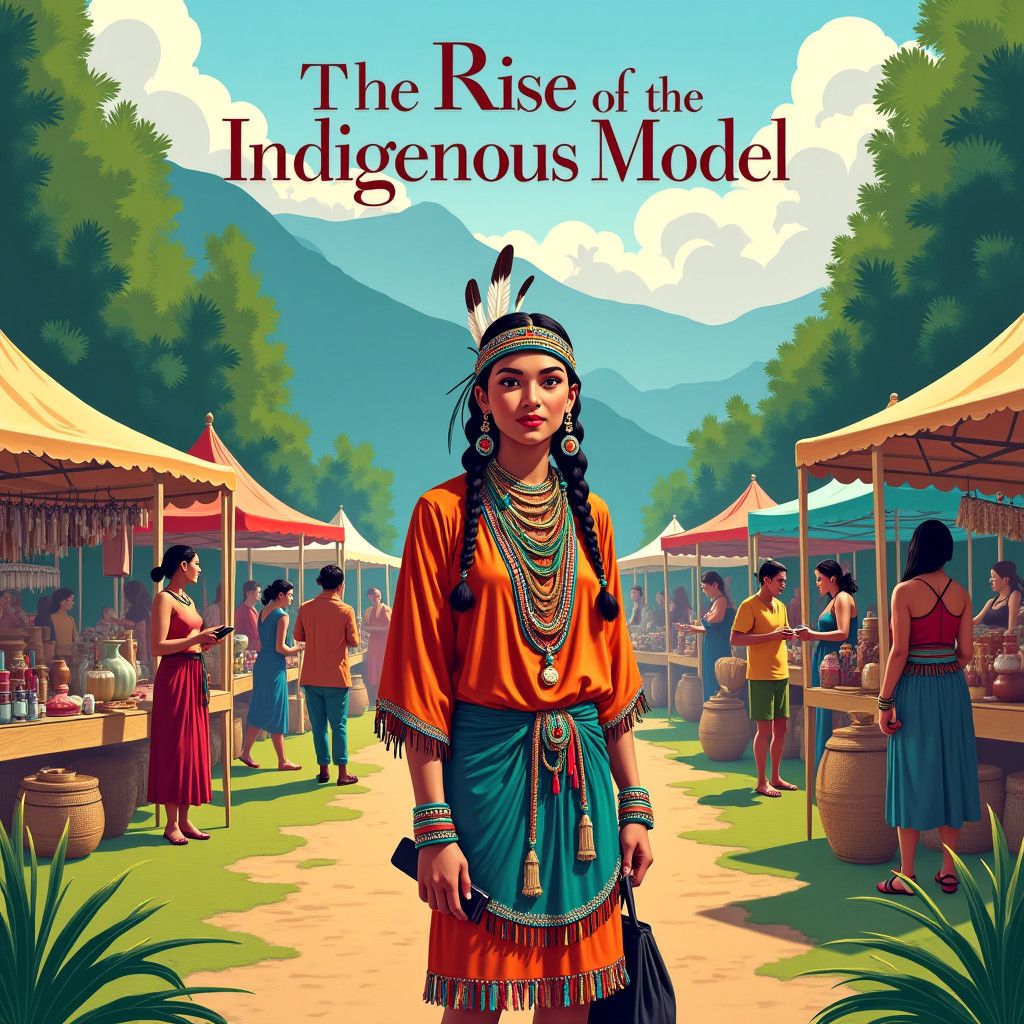

In recent years, the fashion industry has witnessed a significant transformation, particularly in the representation of Indigenous models. This movement gained momentum primarily due to the emergence of Quannah ChasingHorse, a model whose journey began when she was discovered by a Calvin Klein scouting director while advocating for environmental protection. Initially focused on her native culture, ChasingHorse has since illuminated the fashion world, not only through her modeling work but also by addressing the misrepresentation and tokenism that Indigenous peoples typically face.

ChasingHorse, of Hän Gwich’in and Oglala Lakota heritage, burst onto the scene in 2020 when a scouting director was captivated by her passion for environmental activism, which garnered widespread attention. This unexpected recruitment transformed her career and helped launch a wave of Native talent onto the catwalks and magazine covers of major fashion houses, including Vogue Mexico and Chanel.

The representation of Indigenous models has historically been fraught with stereotypes and a lack of genuine understanding. Many brands have perpetuated this issue by hiring models who merely appear Indigenous, often without verifying their heritage. This approach has reduced complex identities into commodified and exoticized stereotypes that mask the rich cultural fabric of 574 federally recognized tribes across the United States. No longer the exception to the rule, ChasingHorse is now a prominent advocate for authentic representation within the industry, emphasizing the importance of respecting Indigenous aesthetics, including long hair, tattoos, and cultural adornments.

“I, as a model, have taken this work very seriously. As I do [it], I make sure I am representing my people. Every single campaign I’ve done, that brand has given back to Indigenous communities,” stated ChasingHorse. These words encapsulate her commitment not only to modeling but also to philanthropic efforts. For instance, many brands that collaborate with her have paved the way for community investment, signifying a shift toward ethical practices in such partnerships.

The period between 2020 and 2024 has seen nearly two dozen Indigenous models cracking into luxury contracts, a remarkable change from the previous norm. Rising stars such as Valentine Alvarez and Denali White Elk have walked for renowned labels like Gucci and Marc Jacobs, while other models like Kylie Van Arsdale have made headlines by featuring on billboards. This surge has highlighted a new era of visibility for Indigenous models in the mainstream fashion context.

Despite this progress, challenges remain. The long-held stereotypes in the industry often persist, influenced by a culture that frequently falls back on outdated narratives. Educators and advocates, including prominent anthropologists, argue that harmful portrayals can either romanticize or misrepresent Indigenous peoples, neglecting their complex relationships with their environments.

In 2016, the Navajo Nation’s successful trademark dispute with Urban Outfitters marked a pivotal moment in the fight against cultural appropriation. This agreement highlighted the need for brands to recognize and respect Native American intellectual property, leading to greater awareness and calls for changes in marketing practices. Some brands, like Ralph Lauren, have taken steps to amend past missteps, collaborating with Native models in recent campaigns.

The emergence of Indigenous solidarity within fashion has fostered a supportive community among Native models. Many shared experiences help combat the “Native omission” phenomenon defined by the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues. Having a presence in editing rooms and on runways allows Indigenous models to shape narratives directly, effectively countering outdated perceptions.

These changes evoke a sense of empowerment, enabling models to establish professional boundaries that honor their cultural values. Diné model Ty Metteba shared her dilemma about leaving her community, stating, “You had to leave the rez (reservation) to model,” reflecting the tension that persists between career opportunities and cultural ties.

Challenges like navigating identity across different cultural contexts remain a reality. Models report inconsistent perceptions of Indigeneity depending on geographical location, resulting in experiences ranging from confusion to outright disrespect. The systemic biases that Indigenous models face highlight the need for further education within the industry.

ChasingHorse’s advocacy extends beyond her immediate experiences. She emphasizes that industry stakeholders must acknowledge the inherent traumas within Indigenous communities, which significantly affect their mental health. This acknowledgment fosters an environment where the unique needs of Native models can be accommodated, promoting inclusivity.

Indigenous representation in fashion is evolving into a vital aspect of broader cultural discourse. While progress has been made, ongoing dialogue about cultural appropriation, ethical representation, and this unique community’s distinctiveness in the fashion landscape will be crucial. As aware allies in the industry begin to respond to these issues, fashion can transition from being a tokenized representation of Indigenous culture into a platform for authentic storytelling.

The path forward is filled with opportunities but still requires vigilance against residual biases. The collective efforts of models, activists, and brands to foster genuine representation signal a promising future for Indigenous narratives in fashion.