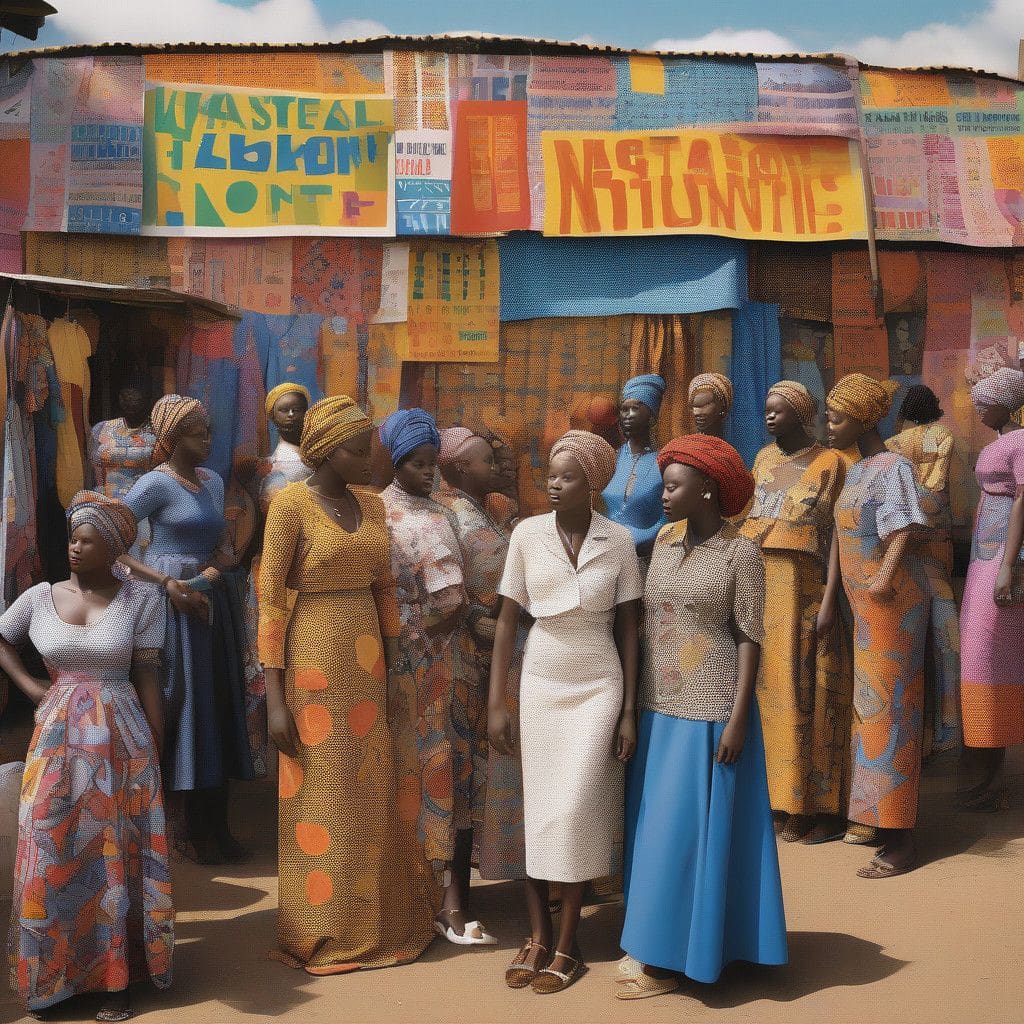

In a significant discourse on sustainability and global trade, representatives from Africa’s used clothing import sector recently challenged prevailing narratives about their industry. Addressing claims that a substantial portion of secondhand clothing imports—up to 40%—ends up as textile waste, these importers provided a contrasting perspective during the inaugural Textile Circularity Conference in Brussels. This robust dialogue highlights the complexities surrounding textile recycling and the critical economic role these businesses play within their communities.

Marlvin Owusu, an executive member of the Ghana Used Clothing Dealers Association, alongside Teresiah Wairimu, chair of the Mitumba Consortium Association of Kenya, voiced their concerns about what they perceive as misleading information. They asserted that the actual figure of low-quality clothing ending up in landfills is only in the single digits. This contention directly challenges the narrative perpetuated by certain sustainability advocates and media outlets that paint their operations as wasteful.

The discourse raised by Owusu and Wairimu underscores an essential dynamic in global secondhand markets. “We are business people… we only import sorted clothes, and we are leading the way on building a circular economy through textile use,” Wairimu stated emphatically. Their words not only highlight the economic importance of this industry but also frame secondhand clothing as a crucial resource in Africa, which is often characterized by price sensitivity in fashion consumption.

Secondhand clothing, known locally as “mitumba,” serves more than just a fashion statement in many African countries—it provides essential employment and affordable clothing options. For many households, these garments offer a practical solution to both economic constraints and fashion desires. In regions where disposable income is limited, the ability to purchase used clothing represents not merely choice, but survival.

Moreover, the broader implications of this ongoing debate touch upon environmental considerations as well. The concept of a circular economy emphasizes sustainability, where reuse and recycling are paramount. Importers like Owusu and Wairimu argue that their operations contribute to reducing waste, a point often overlooked in discussions focused solely on waste generation from imported goods.

The conversation surrounding secondhand clothing is not confined to Africa. Globally, the market for recycled and secondhand clothing is witnessing significant growth. A notable example is the rise of platforms dedicated to reselling pre-owned garments, which have garnered popularity in the wake of heightened environmental consciousness. Companies in Europe and North America have recognized the financial potential in extending the lifecycle of textiles rather than relegating them to landfills.

A recent report on the fashion market illustrates a fundamental shift, revealing that consumers are increasingly inclined towards sustainable options. According to research by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, extending the lifespan of clothes by just nine months can reduce carbon, water, and waste footprints by 20-30%. This aligns with the claims made by African importers, asserting that their businesses are part of a global solution rather than a problem.

The intersection of global trade and local initiative can lead to innovative models that capitalize on sustainability. For instance, initiatives that enable communities to engage in the sorting and distribution of secondhand clothing have the potential to create jobs while promoting environmental stewardship.

It’s also imperative to acknowledge the growing consciousness of consumers regarding the origins of their apparel and ethical consumption. This shift towards a more thoughtful approach to fashion provides an avenue for secondhand clothing to shine—not as a low-quality alternative but rather as a preferred choice for environmentally conscious shoppers.

As discussions around these claims continue, it is essential to consider the broader context of Africa’s role in global textile trade. Insights from industry leaders like Wairimu and Owusu signal a collective ownership of the narrative pertaining to the secondhand clothing sector, urging stakeholders and consumers alike to rethink waste, value, and sustainability. Their commitment to quality and economic empowerment within their communities paints an image of an industry more aligned with global sustainability goals than previously imagined.

This ongoing debate may catalyze policy discussions that affect how governments and organizations approach the issue of textile waste and management globally. By amplifying the voices of those directly affected, such measures can be more effectively directed towards fostering genuinely sustainable practices that benefit all stakeholders involved.

In closing, the narrative surrounding used clothing in Africa is not merely about waste but rather about employment, economic development, and a commitment to sustainability. By aligning the business goals of local importers with global sustainability initiatives, this sector stands on the cusp of transforming public perception, driving demand for secondhand clothing, and reshaping the future of fashion in a way that is both economically and environmentally beneficial.